“Why a country once on the brink of democratic renewal now faces state collapse — and what it will take to reverse course”

Sudan did not arrive at its current catastrophe by accident. The country’s descent from the hope of the 2018 revolution to the devastation of today’s military conflict stems from two interlocking failures. The first was the breakdown of the post-revolutionary civilian-military partnership, driven in large part by the military leadership’s resistance to dismantling the political-economic order built by the deposed Ingaz regime—an Arabic word for “salvation”. The second was the fragmentation of the military establishment itself, culminating in a violent power struggle between the regular Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The “December 2018 Revolution,” as the Sudanese call it, was the country’s largest mass uprising, bringing an end to 30 years of kleptocratic rule. Yet the deeper structures of Sudan’s militarized political economy—particularly the networks controlling gold, state-owned enterprises, and strategic trade—remained intact (Elbadawi and Alhelo, 2023; Elbadawi et al., 2023). The transition thus produced a paradox: a civilian-led government without full sovereign authority, and an economy still dominated by armed actors who viewed reform as a direct threat to their rents.

The civilian cabinet pursued macroeconomic stabilization, exchange-rate unification, the removal of fuel subsidies, and debt relief under the HIPC initiative – a pathway that would have erased nearly $50 billion of Sudan’s more than $60 billion in external debt. However, the process required dismantling the military-security economic complex and transferring its assets to the Ministry of Finance. The result was predictable: the military staged a coup in October 2021, ending the democratic transition and paving the way for today’s war.

The economic roots of state failure: oil, gold, and the political marketplace

Sudan did not suffer only from a resource curse; it also suffered from a governance curse. Oil revenues financed regime survival rather than national development.

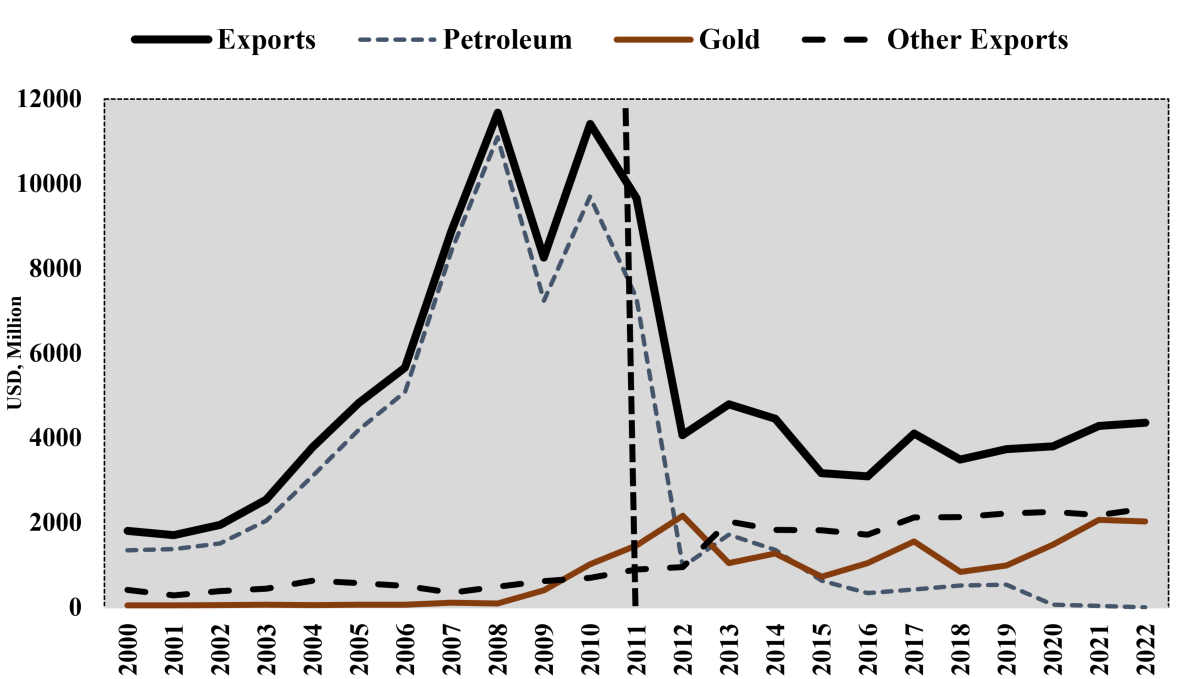

During the oil boom (1999–2011), income was not invested in productive capacity but used to purchase political loyalty. Alex de Waal’s (2019) concept of the “political marketplace” – a system of rule based on cash, coercion, and transactional patronage – effectively became the state’s operating logic. The secession of South Sudan in 2011 removed three-quarters of Sudan’s oil income, producing what Elbadawi et al. describe as an extreme case of a “sudden stop”: GDP contracted by 50 percent, inflation surged, and a militarized gold economy emerged, controlled by networks linked to both the SAF and the RSF. Sudan’s export capacity collapsed after 2011 (Figure 1), with the current-account adjustment exceeding even that of Latin America’s crises in the 1990s.

Gold replaced oil as the rent that sustained the political marketplace – but unlike oil, it was fragmented, off-budget, and deeply militarized. The state continued to function as an arena for rent distribution rather than a vehicle for public investment.

Figure 1. Collapse of Sudanese Export Capacity Post 2011 (USD, Million)

The war of the two armies and the collapse of the republic

“Sudan is not only at war; its statehood is eroding in real time.”

This is not a classic civil war. It is a factional military conflict between two forces engineered by the same regime: the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the formal national army, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), initially created as a counter-coup militia and later formalized as a parallel army. When negotiations over force integration collapsed, the guns turned inward – not in the peripheries, as in previous wars, but in the capital itself, before spreading to other major cities.

Unlike traditional low-intensity civil wars, this conflict resembles an inter-state war in both scale and intensity. Its consequences are catastrophic. The humanitarian toll is staggering: 13 million internally displaced people, 3.4 million refugees, 16.5 million children out of school, and 30.4 million people projected to require humanitarian assistance in 2025 (WHO, UNICEF). The war is also destroying the very foundations of the state – its ministries, archives, universities, and the remnants of its formal productive economy.

“If war persists, the question will not be whether Sudan recovers, but whether Sudan still exists as a unified territory.”

Using the World Bank’s Long-Term Growth Model (LTGM), Elbadawi and Fiuratti (2024) simulated the economic cost of war under two scenarios. Under a counterfactual of 4% annual growth without war, a 15-year conflict would cost Sudan more than USD 2.2 trillion in lost output – 66 times the size of its 2022 economy. Even a five-year war would erase USD 271 billion in potential GDP, more than eight times pre-war output. Recovery would be painfully slow: convergence to the no-war trajectory would take 19 years (until 2043) after a short war, and 55 years (until 2079) after a prolonged one. Even when measured against a stagnant baseline, the losses remain enormous: USD 52 billion for a five-year war and USD 189 billion for a fifteen-year one.

| Table 1: Simulated costs of Sudanese civil war for two peacetime growth counterfactuals | ||

| War Duration | Relative to Stagnant Growth Rate (at 2022 GDP level) | Relative to GDP growing at 4% from 2022 |

| 15-year War | 189 billion (convergence achieved by 2047) | 2.2 trillion (convergence achieved by 2079) |

| 5-year War | 52 billion (convergence achieved by 2034) | 271 billion (convergence achieved by 2043) |

Source: Elbadawi and Fiuratti (2024).

What a real exit requires

A credible pathway back to peace and development requires three simultaneous transitions:

- A political settlement anchored in civilian legitimacy. Not another power-sharing deal between generals and pro-democracy forces, but a broad civic coalition – backed by regional and UN guarantees – capable of demobilizing the war economy and rebuilding the state on new foundations.

- A new economic social contract. Legitimacy must come from public goods and productive growth- not fuel subsidies, patronage networks, or militia-controlled gold rents.

- A growth model rooted in Sudan’s real comparative advantage: agriculture. The future lies in agro-industrial corridors, logistics, and regional food markets – not extractive mineral exports. Sudan still retains the core attributes of a late-industrializing agricultural powerhouse: 200 million feddans of arable land, direct access to the Red Sea, a young labor force, a strategic position connecting the Sahel, Gulf, and Horn of Africa, and rising global demand for food security and near-shoring of production.

Under peace, Elbadawi and Fiuratti project a phase of “renaissance growth,” led by FDI in agro-industry, rail, energy, and water systems – an adapted Sudanese version of the Vietnam/Ethiopia model.

Sudan at the threshold

“Sudan is suspended between two futures. Which one prevails will not be determined by who wins in the battlefield, but whether peace is built around power – or around a people”

In one future, the war deepens, fragments, and ethnicizes the country, dissolving it into militia fiefdoms, famine zones, and regional bargaining. The state survives only as memory- or at best resembles Libya’s divided reality: an eastern-central zone under SAF control and a western zone under RSF rule.

In the other future, the war is halted before disintegration becomes irreversible. A civilian compact – underwritten by regional and UN guarantees – dismantles the war economy and re-anchors legitimacy in development rather than coercion. One path ends with borders erased and archives burned. The other begins with the first credible project of national renewal since independence.