For scholars and practitioners of the international economy, conflict and underdevelopment are two increasingly intertwined phenomena. Concerned about low-income countries? Two-thirds of them now fall under the World Bank’s Fragility and Conflict-Affected Situations (FCS) classification. Trying to address global food insecurity? The same FCS countries are home to about 75 percent of the world’s acutely food-insecure people. The geography of deprivation appears to have shifted: it now largely overlaps with the geography of violence. The question, then, is not whether conflict and development trajectories are linked—but how they became so tightly bound.

The road behind

The convergence of conflict and economic deprivation can be traced to two global forces—one remarkably positive, the other tragic.

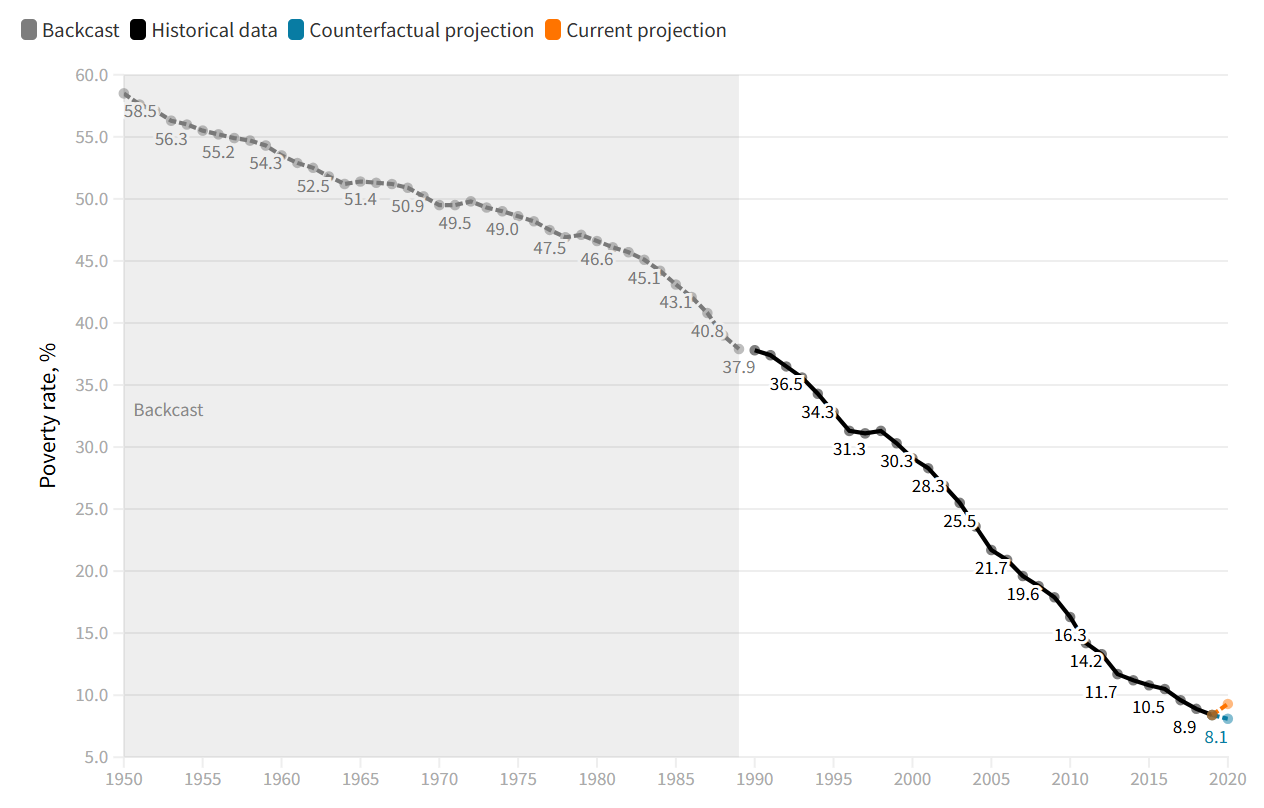

The first is the extraordinary progress in reducing poverty since the Second World War. As shown in Figure 1, the share of the global population living in extreme poverty—below $2.15 a day in 2017 dollars in purchasing power parity terms—has fallen steadily from nearly 60 percent in the 1950s to just over 8 percent in 2020. This transformation, achieved within a single lifetime after millennia of stagnation, is historic. While reducing extreme poverty is not the end of the development process—and the desire for faster growth is understandable—these concerns should not obscure the sheer scale of progress: Billions have been lifted out of destitution, not a small feat.

The second, far darker trend is the devastating impact of conflict on economic development. Once violence takes hold, it is hard to avoid “development in reverse,” a term coined by Paul Collier. On average, people living in FCS countries currently earn about $1,500 a year, compared with $6,900 in other developing economies. Moreover, this gap is widening: incomes in FCS countries have stagnated since 2010, while those in non-FCS developing countries have doubled. Unsurprisingly, the extreme poverty rate in conflict-affected countries remains close to 40 percent.

Together, these two dynamics have driven a concentration of the toughest development challenges in conflict-affected states. While important work continues in non-FCS developing countries, the hardest economic battles are fought alongside violent ones.

Figure 1. The global incidence of extreme poverty, 1950-2020.

The road ahead: Will necessity drive innovation?

In the coming decade, the development landscape will likely be transformed further by two emerging dynamics.

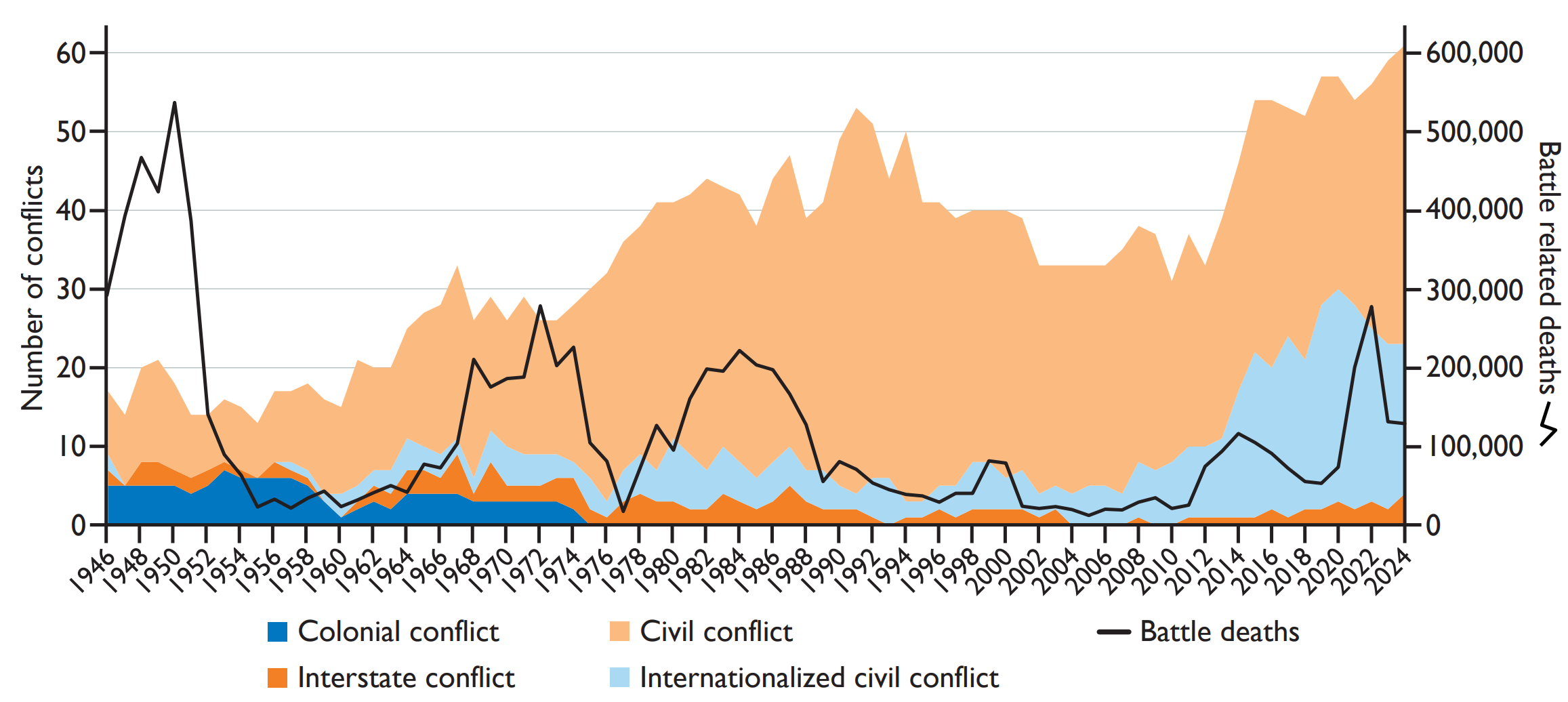

The first is the renewed escalation of violent conflict. According to the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), both conflict events and battle deaths have risen since 2010. The past four years (2021-24) have reportedly been the most violent period since the end of the Cold War, with nearly 740,000 confirmed battle deaths (Figure 2). The composition of warfare has also changed: civil wars are increasingly internationalized, while inter-state confrontations—once considered unlikely—are re-emerging. Further, the possibility of direct military confrontation among major powers can no longer be dismissed.

The second challenge is the contraction of global aid flows. In 2024, Official Development Assistance (ODA) from OECD countries declined by 7.1 percent in real terms. For major contributors like United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, this was reportedly the first decrease in nearly 30 years. The OECD currently projects a further 9 to 17 percent reduction in 2025.

Taken together, these trends clearly show the imperative of “doing more with less” in promoting development. When output needs to grow, but inputs are shrinking, the only way to succeed is to become more effective. How this can be achieved in FCS contexts will dominate the policy discussions in the years ahead. The Development Front seeks to contribute to this conversation.

Figure 2. State-based conflict events and battle deaths: 1946-2024.

Development Front

This platform was established to help foster dialogue around critical problems in conflict and development. It aims to merge perspectives from economic research, policy, and practice.

Economic research, like any scientific field, is prone to attention bias—it gravitates toward problems that its tools can already solve. As a result, it can risk ignoring factors that may matter most but are not measured well. The parable of Nasreddin Hodja, the 13th century Anatolian folk philosopher, is instructive: after losing his ring indoors, he searched for it outside because he could see better under bright daylight in his courtyard.

Yet development policy does not fare much better on its own either. Without guidance from economic theory and empirical evidence, development strategies are lost in a chaotic universe of interlocking forces.

To help bridge that divide, the Development Front will publish contributions in four categories: research highlights, policy notes, reviews, and opinion essays. It will also feature Echoes of War, showcasing student photo-journalism projects that document human resilience in the shadow of conflict. These projects are supported by the Conflict and Development Program at Texas A&M University, with funding from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation.

In a world where conflict increasingly defines the boundaries of development, The Development Front aims to promote a more integrated understanding—one that recognizes peace and prosperity not as sequential goals, but as joint conditions for sustainable development.