As 2026 unfolds, the landscape of post-conflict reconstruction is being reshaped by the growing prominence of private investment alongside traditional public donor commitments. The surge in announcements from private enterprises and state-owned funds signals a potential shift in how capital is mobilized for fragile states. Recent examples in Gaza, Syria, and Ukraine are demonstrating that private commitments can even surpass those of governments. While the actual inflow of funds often lags rhetoric, the very act of announcing substantial foreign direct investment can serve as a catalyst. Large investment announcements by trusted, known, and deep pocketed private corporations and sovereign wealth funds can in theory accelerate peace processes, foster stability, and attract further capital inflows.

The historical practice

Since the Second World War, most postwar reconstructions generated little interest from private investors, who oftentimes had little available capital to risk in countries with fragile security situations and weak institutions. While some frontier investing into conflict and immediately post-conflict zones occurred at the margins, the vast majority of funds for post-conflict reconstruction came from public coffers of the international community. These funds commonly filled fledgling governments’ treasuries for the delivery of basic services, such as developing administrative agencies, infrastructure, and helped enforce laws for physical and economic security for their people. Importantly, these public funds were generally more focused on social, rather than financial returns pursued by FDI – building trust, enhancing the legitimacy of the state, and laying the groundwork for less risky private investment.

This type of overseas development assistance (ODA) typically came in the form of grants, direct humanitarian supplies (food aid, medicines, etc.), and was administered by a mix of multilateral, global institutions and individual nation state donors. Globally, official ODA inflows were higher in the most fragile regions with the least strong institutions. An earlier OECD analysis found that in fragile, post-conflict states, ODA was double the volume of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the first two decades of the 21st century. In extremely fragile states, the level of traditional development assistance was even higher, with eleven times more ODA coming in than FDI.

Is there a shift?

In the last two decades, as economists emphasized the importance of sustainable economic growth as a force in national propulsion, governments increasingly used loan guarantees as part of recovery packages to de-risk private enterprise development. Loan guarantees backing private investment in fragile states has increased nearly sevenfold from the World Bank alone, from $1 billion in the early 2000s to over $9 billion by 2025.

In 2025, many of the largest FDI announcements into post-conflict countries were from largely private enterprises or state-owned investment funds. Outside of substantial pledges from individual countries, the European Union & European Commission, or international finance institutions such as the World Bank Group and International Finance Corporation (IFC), private investment has been a leading source of capital. In the cases of the regions characterized by still-active conflicts and frequent civil unrest, including Gaza, Syria, and Ukraine, private investment announcements have rivaled – and in Syria’s case eclipsed – those of governments.

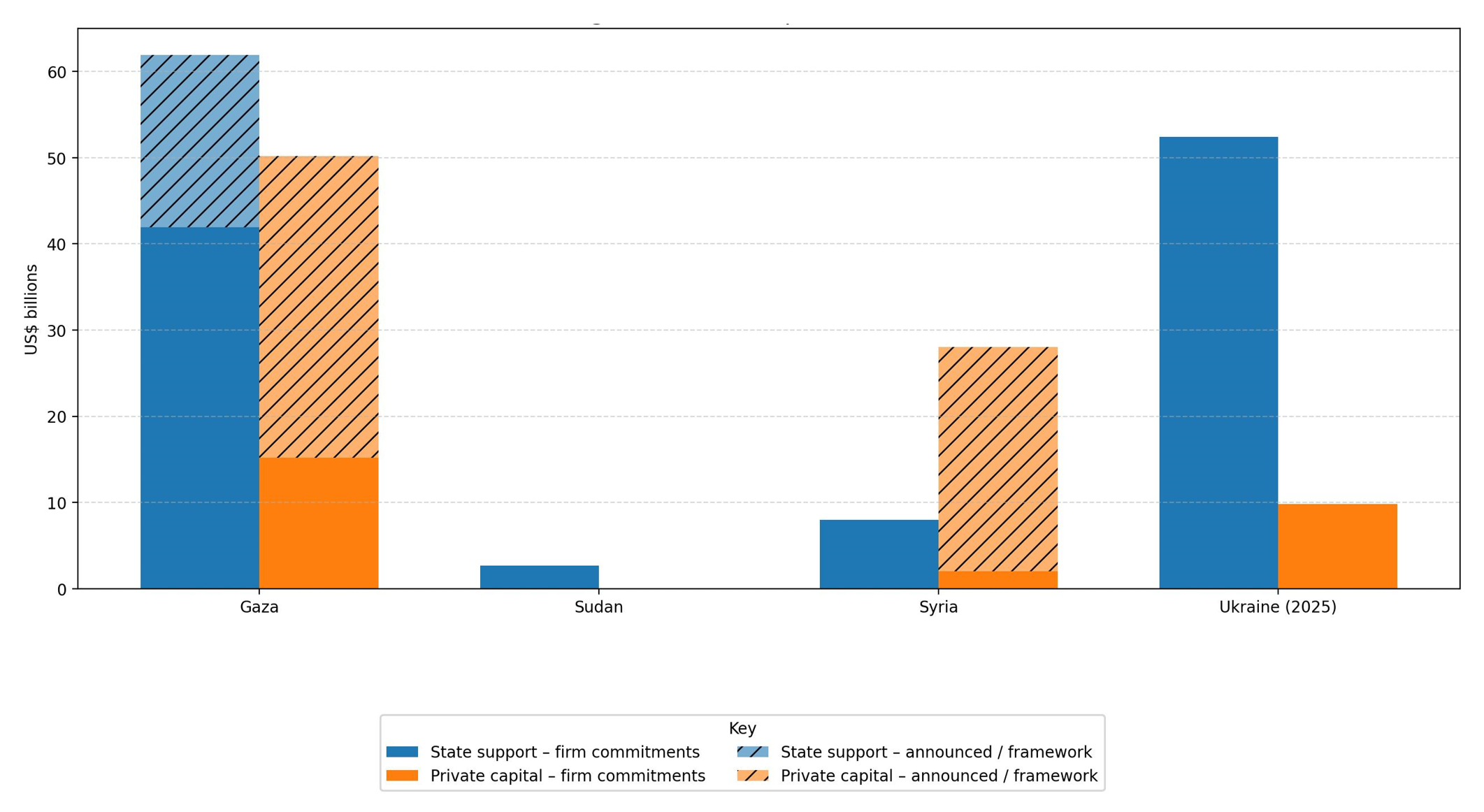

While there is no official record of all investment announcements to date, taking stock of these public announcements shows a remarkable interest from private investors and sovereign wealth funds flow for economic development to these fragile states (Figure 1). Reports of the most recent peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine have American envoys offering to unlock $800 billion in investments in reconstruction funding for Ukraine. Out of the $6 billion of official assistance announced at the Europe donor conference in March of 2025, over 20 percent was structured as loan guarantees for private investment.

A mix of foreign government pledges and private investments of over $28 billion for Syria’s new government were signed in 2025, and private investment – including $800 million for the development of its ports, deals in oil & gas, tourism and other sectors are emerging. In November, the company who earlier announced a ports deal with Syrian authorities confirmed that it had begun operations at the Port of Tartus with newly appointed leadership. The most recent talks for the Gaza Strip’s reconstruction have included estimates of $50 billion dollars of private investment over the next ten years, with the US serving as the anchor investor of the first 20 percent of a mix of grants and sovereign debt proposed at over $112 billion in total funding. In the most recent (and very much still evolving) case of Venezuela, the US government has announced its intention for US private investment to play a substantial role in the rehabilitation of production for the world’s largest oil reserves.

Figure 1. Official funding and private capital mobilization announcements, 2025

Notes: Data excludes a reported, but not yet formalized announcement of an additional $800 billion in private capital flows that would be directed to Ukraine following a peace agreement.

The role of announcements

Large-scale pledges, whether from private enterprises or public donors, can play a pivotal role in shaping expectations, building confidence, and encouraging further engagement from both domestic and international actors. Even when actual capital inflows remain limited, the signaling effect of such commitments, which serve as strategic communication, can initially help motivate peace and stability, and strengthen the resolve of governments and communities in transition.

In his exhaustive analysis, The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War, Benn Steil finds that the primary motivation of the Plan’s chief architects – George Kennan and William Clayton – was to instill a collective psychological boost to its European partners and demonstrating long term commitment to stability by the United States. These elements were seen as more fundamental to the success of rebuilding than the actual infusion of investment. As Steil writes,

“The funds themselves were not originally intended to be more than a pump primer. The Plan’s architects, Kennan and Clayton in particular, believed that a multiyear program of assistance was necessary to establish confidence in a long-term American commitment to European recovery and security, to reduce political and social resistance to vital structural policy reforms, and to ease the reintegration of Germany into Europe’s economic architecture. Kennan had argued from the outset that Europe’s problems were “psychological,” and that the primary stimulative effect of the Marshall Plan would come from beneficiaries seeing that the United States was committed to helping restore them as free and independent nations.”

As the international community looks to bring definite, lasting conclusions to still-active conflicts and provide sustained revenues to support nascent governments and prosperity for citizens, how can announcements of FDI be best positioned to maximize secondary returns to stabilizing, emerging economies?

Research indicates that FDI can help countries escape poverty–conflict traps by injecting capital and jobs, rebuilding productive capacity and state revenues, while strengthening incentives for stability and reducing risk of renewed violence. At the same time, the psychological and expectations-driven effects of announcements of FDI and loan guarantees—before funds are fully deployed—remain underexplored and should be studied much more in depth as potential upstream catalysts for recovery.

This dynamic echoes lessons from history, notably the Marshall Plan, where the psychological impact of sustained commitment and confidence-building measures proved as vital as the financial resources themselves. The architects of the Plan understood that long-term stability and reform required more than just money—it demanded a visible, credible promise of partnership and support. Today, the international community faces a similar challenge: leveraging the power of investment announcements not only to inject capital and create jobs, but also to instill hope, encourage reforms, and signal enduring engagement with countries emerging from conflict.

With these aims in mind, a primary question is whether the lift brought by private investment can be sufficient to generate the social impact pursued by ODA typically targets. The dissolution of the Soviet Union provides important warnings for this, where laissez faire economic policies and a significant lack of emphasis on ODA dominated global efforts. With poor investment in institution-building and regulatory and anti-trust practices, many assets ended up in the hands of very few oligarchs in a newly capitalist economy. Similarly, an overemphasis on the positive effects of market forces without as significant levels of FDI led to a negative initial impression of capitalism for many Russians.

Looking ahead

Will 2026 mark the year that initial private investment announcements begin to fully catch up with large scale public donor commitments for post-conflict reconstruction? As the world looks at the ongoing governmental transition in Venezuela, and the increasing civil upheaval in Iran, could figures of FDI supporting the world’s respective number one and number three levels of proven oil reserves eclipse 2025’s figures?

While most of the announcements and pledges of significant FDI are still in the realm of initial intentions with little actual inflows recorded on the ground, what effect do the announcements have on helping to accelerate movements towards peace in countries still in end stages of conflict? And how do the promises of significant economic investment serve as a force for stabilization while spurring additional capital inflows? While Syria has demonstrated productive capacity for energy, and reconstructing Gaza may provide lucrative opportunities for construction businesses, neither country is resource-rich or natural investment targets at a significant level. Yet their geographic neighbors are demonstrating the value they place in their shared regional future through announcing financial and other commitments. Policymakers and investors must recognize that the expectations and psychological effects of investment pledges—before any funds are deployed—can play a decisive role in shaping recovery trajectories. However, rigorous research is needed to better understand these upstream effects and to design strategies that harness both the tangible and intangible benefits of private capital. To fully benefit from a more private-investment driven process, a nuanced approach must be taken to maximize the secondary returns of FDI in these environments. Ultimately, the interplay between public and private finance, and the strategic use of investment announcements, will likely be used in unlocking sustainable growth, resilience, and leading to peace in post-conflict societies.