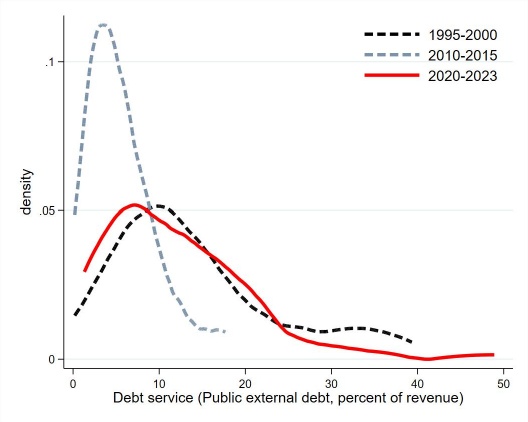

Over the past decade, developing countries have, once again, turned out in debt distress. Debt service levels now approach those recorded in the late 1990s (see Figure 1, panel A), before the sweeping cancellations of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiatives (MDRI).

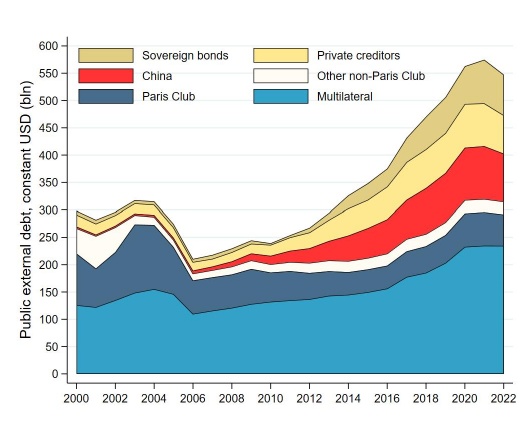

If today’s debt ratios resemble those of the pre-HIPC/MDRI era, the creditor landscape has changed profoundly. Multilaterals still play a central role but, starting from the 2010s, China has emerged as the dominant bilateral lender, while traditional Paris Club members have scaled back (see Figure 1, panel B).

Figure 1. The new debt landscape: Rising debt service and change in creditor composition

Notes: Panel A plots the distribution of the average of the ratio of debt service on public and publicly guaranteed external debt over revenues over three periods of time and across the 68 DSSI-eligible countries. Panel B plots the amount of public and publicly guaranteed external debt (in constant 2017 USD) by creditor type. See Cordella, Cufre and Presbitero (2026) for details.

This new configuration could complicate any future debt workouts. During the HIPC/MDRI era, coordination involved a small group of Western-led institutions—the IMF, World Bank, traditional Regional Development Banks, and the Paris Club—allowing decisions to be mainly made along the Washington–Paris route. Any comparable effort today would also have to involve Beijing, now the largest bilateral creditor, potentially adding complexity and geopolitical tensions.

The free-rider worry

Beyond today’s geopolitical rivalries, the current context revives the old “free-riding” concern; that is, debt relief could encourage new creditors to step in once fiscal space is created, diluting its impact. During the HIPC and MDRI years, this fear focused mainly on private creditors, seen as potential free riders on official forgiveness. As China’s overseas financing expanded rapidly afterward, what had once been a concern about private markets became a story about China.

This concern persists in Washington policy circles. At the 2023 World Economic Forum, World Bank senior staff expressed a widely held view: “the countries that were hitherto in debt found new life following the relief they got from the HIPC. The write-offs in the 1990s allowed them to restart their borrowing spree with a temptation to turn to non-traditional creditors,” that is, China.

But is this narrative supported by facts? Did China expand its lending because of debt relief, effectively free riding on the space created by others? Or was the timing coincidental, driven by China’s growing role in international development finance rather than by debt relief itself?

This question is at the heart of our paper, “The HIPC Initiative and China’s Emergence as a Lender: post hoc or propter hoc?”—recently published in the Journal of Development Economics—where we construct a counterfactual of what would have happened to credit flows had HIPC and MDRI relief never occurred, and we use it to assess the effect of debt relief on credit flows. More precisely, we resort to the synthetic control method to compare each HIPC country with its “synthetic twin”—a weighted combination of similar countries that did not receive debt relief.

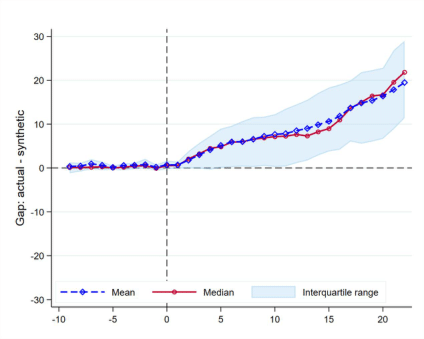

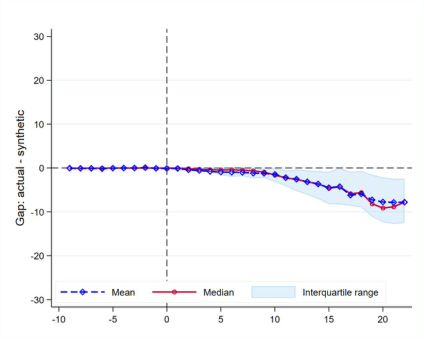

The results, summarized in Figure 2, reveal a striking pattern. Multilateral institutions kept their pledge to increase support (panel A), while—contrary to common wisdom—Chinese net flows to HIPCs fell relative to those to non-HIPCs, after debt relief (panel B). Of course, this does not mean that China decreased its lending to HIPC countries. China’s lending might have increased every country (and it indeed increased in most), but, if this was the case, it increased less in HIPC than in non-HIPC. In summary, total net flows to HIPCs increased only moderately after relief, driven almost entirely by multilaterals. Flows from China and other non-Paris Club creditors declined. As a result, international financial institutions expanded their exposure, while China’s and private lenders’ shares fell. In short, rather than China “jumping in,” it was the multilaterals that stepped up.

Figure 2. Net flows post HIPC initiative, by creditor type

Notes: Each panel plots the difference between the actual net flows by a specific creditor (multilaterals in panel A and China in panel B) and those of the respective synthetic control (gap). The solid red line is the median value of the gaps in the sample of HIPCs; the dashed blue line is the average. The shaded areas indicate the interquartile range. The vertical line indicates the country-specific HIPC decision point. See Cordella, Cufre and Presbitero (2026) for details.

Explaining the pattern in the data

How can we interpret these results? Our first conjecture is a geopolitical one.

Many countries that later qualified for HIPC relief had long-standing aid relationships rooted in post-colonial or strategic ties. Once these ties could no longer be maintained through debt accumulation and defensive lending, new assistance might have been used to preserve influence or attract countries into new spheres of alignment. If that were the case, debt relief should have been followed by larger inflows to countries geopolitically close to major donors, and this could explain why Western-led multilateral institutions increased their exposure. Yet our evidence rejects this view. Using a measure of political alignment based on UN voting patterns, we find no systematic difference in post-relief net flows between countries that are close or distant to either China or the United States. The same holds when countries are grouped by natural-resource wealth.

The second conjecture stresses the irrelevance of debt levels as a determinant of assistance flows; that is, donors may not adjust their support according to how indebted a country is. This is because net flows are typically positive—recipient countries receive more in new financing each year than they repay—and this creates a strong incentive to avoid default, making debt stock irrelevant. Moreover, in low-income countries with weak governance, as high debt does not necessarily hinder investment or growth, debt relief does little to alter perceptions of creditworthiness and thus to attract additional resources.

Multilateral creditors, by contrast, operate under different incentives. Since 2005, with the adoption of the MDRI, the World Bank and IMF have guided lending through the joint Debt Sustainability Framework, linking the terms of new financing to a country’s debt-distress rating. When HIPC and MDRI reduced debt stocks, those ratings improved, allowing a greater share of loans relative to grants and thus increasing net flows. Internal incentives reinforced this dynamic. Project and country teams are often rewarded for maintaining or expanding lending portfolios rather than for restraint. The post-HIPC rise in multilateral flows reflects both the fiscal space created by debt relief and the institutional drive to sustain operations—consistent with their “additionality” pledge.

Conclusions

Our analysis finds no evidence that China or other emerging creditors increased their lending because of debt relief under the HIPC and MDRI initiatives. On the contrary, net flows from these lenders declined, while multilateral institutions expanded their financing, probably because of institutional incentives rather than geopolitical motives. To conclude, our paper provides new evidence that debt relief reshaped the composition of lending, but not in ways consistent with geopolitical competition or with the widespread view that China free-rode on Western debt forgiveness.

Hence, understanding the effects of the HIPC and MDRI may help frame current debt debates with fewer preconceptions, though it leaves open more questions than it resolves.