Many developing countries have invested heavily in expanding access to technology in hopes of boosting children’s educational outcomes. Despite these significant public and private commitments, research has produced mixed findings: some studies report positive impacts (e.g., Muralidharam et al. 2019; Araya et al. 2025), others find no detectable effects (e.g., Beuermann et al. 2015; Piper et al. 2016), and some even document negative impacts (e.g., Linden 2008; Malamud and Pop-Eleches 2011).[1] Yet, apart from a few notable exceptions (e.g., Lakdawala et al. 2023; Yanguas 2020), most of this evidence comes from short-term evaluations.

A widely publicized effort to distribute personal laptops to students in developing countries was the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) initiative, implemented in more than 40 nations. A large-scale experimental evaluation of the OLPC rollout in Peru found no impact on primary school achievement or enrollment after 15 months (Cristia et al., 2017). In this study, we extend that earlier work by assessing the long-term effects of the OLPC program in Peru (Cueto et al., 2025). Using a combination of administrative records and survey data, we tracked a new sample of students across 531 schools over a 10-year period.

Even if short-term academic gains are not immediately apparent, increasing access to technology in schools may influence longer-term outcomes in two distinct ways. First, schools themselves may experience delayed effects as teachers and administrators gradually learn to integrate technology more effectively into instruction.[2] Second, students may be affected as they advance through the education system: greater exposure to computers can shape their attitudes, behaviors, and a wide range of skills, potentially leading to larger impacts on later educational outcomes. Accordingly, this study investigates the long-term consequences of expanding access to personal laptops within schools on both schools’ academic performance over time and students’ educational pathways from primary through tertiary education.

Our experimental study

We investigated 531 rural primary schools that were randomized into 296 treatment schools and 235 control schools. Treatment schools were assigned to participate in the OLPC program which provided students with personal laptops (called “XO laptops”) starting in 2009. These low-cost durable laptops were specifically designed for learning and came loaded with about 200 e-books and 39 applications.[3] In addition, students were allowed to take their laptops home with about 20 percent doing so.

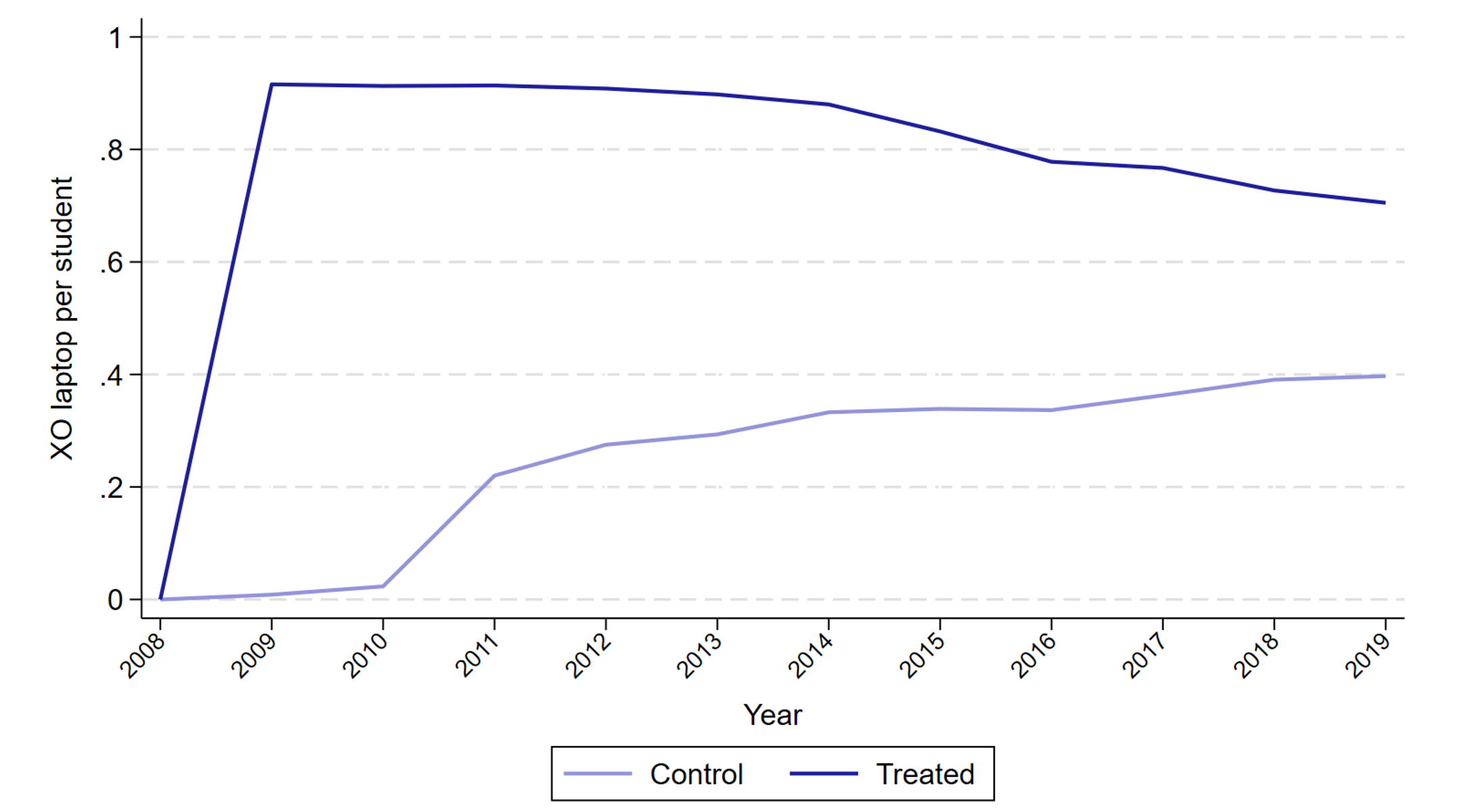

Using administrative data, Figure 1 shows that the program increased the ratio of XO laptops to students in treatment schools from 0 to almost 1 by the end of 2009. Starting in 2011, some laptops were also distributed to schools in the control group so that the average ratio of XO laptops per student in these schools eventually reached 0.4 by 2019. There was also a decline in the ratio for treatment schools over time. Still, the marked difference in access to laptops between treatment and control schools remained.

Figure 1. XO Laptops per Student over Time

Effects for Schools over Time

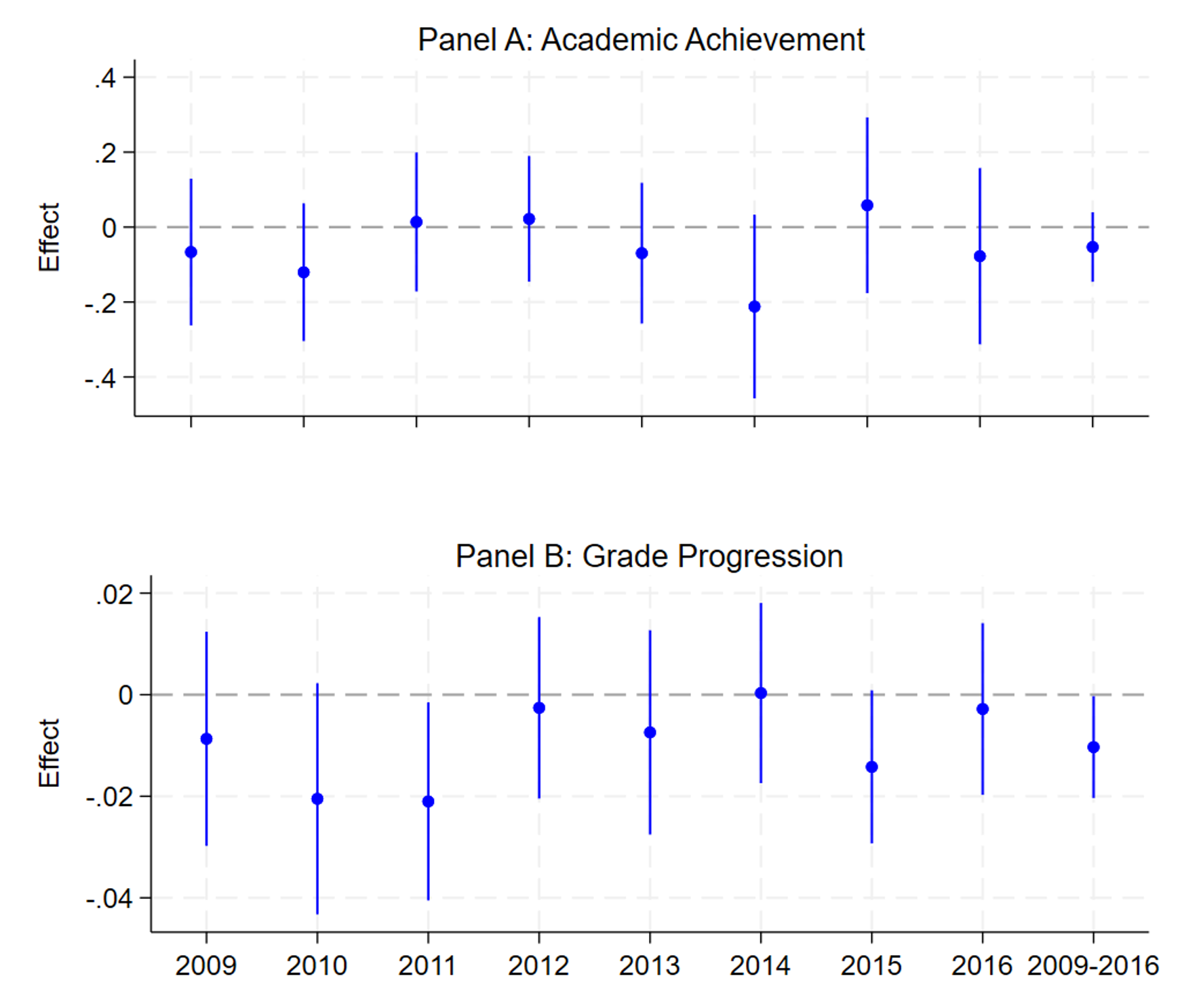

We began by examining how the OLPC program affected schools’ academic performance between 2009 and 2016, using annual second-grade national assessments in mathematics and reading. As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, the results reveal no significant impact on overall achievement (averaged across both subjects), nor any consistent pattern of effects across years. When pooling all years of data, we find negative but statistically insignificant impacts, allowing us to rule out positive effects exceeding 0.05 standard deviations in math and 0.03 standard deviations in reading at the 95 percent confidence level. Overall, the evidence provides little indication that the OLPC program improved schools’ academic outcomes over time.

Figure 2. Effects for Schools over Time

We additionally assessed the impact of the OLPC program on the share of primary students who advanced to the next grade from 2009 to 2016, drawing on data from annual school censuses. As presented in Panel B of Figure 2, the estimates are generally negative, though typically not statistically significant. The pooled results indicate a 1.0 percentage-point decline in grade progression, suggesting that introducing one-to-one computers into classrooms may have had some adverse effects on students’ advancement.[4]

Effects on Student Educational Trajectories

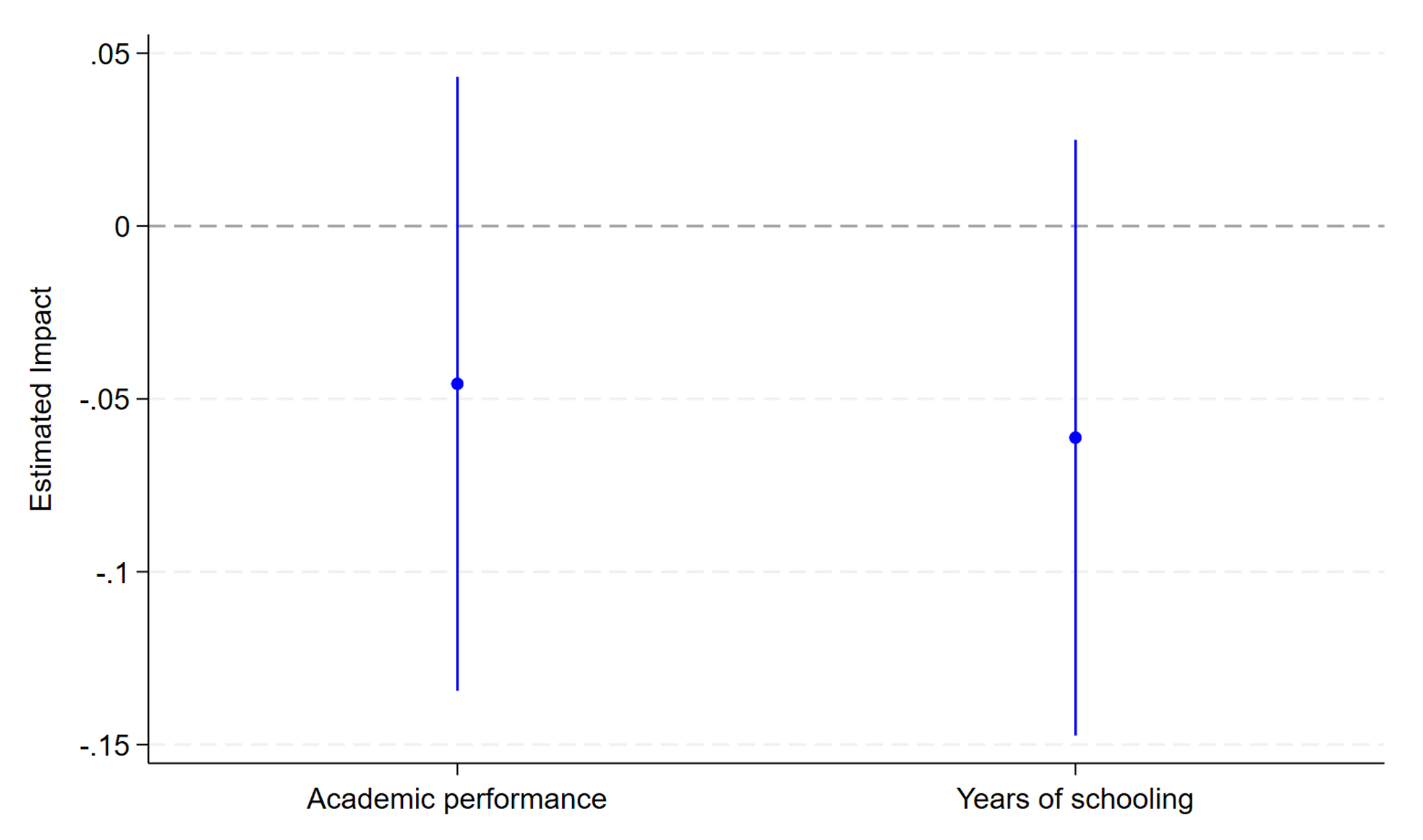

We then assessed the impact of the OLPC program on educational trajectories as students progressed through the school system. We obtained data from 4th and 8th grade national exams, from 5th and 6th grade tests that we administered in a subset of schools, as well as longitudinal administrative data on grade progression from primary to tertiary education. To summarize the results and address concerns related to multiple hypothesis testing, we constructed one measure that averaged all the exams and tests (“academic performance”) and one measure that calculated the number of completed years of schooling (“years of schooling”) for all cohorts through 2019. The estimated impacts on these two measures are shown in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3. Effects on Student Educational Trajectories

We observe that the estimated impacts on academic performance and years of schooling are both negative and insignificant. There is no evidence that the OLPC program improved educational outcomes of students over time.

Discussion

Why did the OLPC program not improve academic achievement or educational attainment? To address this question, we examined survey data that we collected from a subset of 140 schools in 2013. The survey data suggests that although teachers in OLPC schools were more likely to receive training, their digital skills did not improve, and classroom use of laptops increased only modestly. Students did use the laptops more at home and showed better device-specific digital skills, but their broader cognitive skills did not improve. Overall, the program led to limited academic use of laptops and produced few gains beyond basic digital literacy, which likely explains the lack of impact on achievement and attainment.

Conclusion

As developing countries continue expanding access to computers and the internet, it is crucial to examine long-term educational impacts. Our study of the OLPC program in Peru found no positive effects on school performance or student educational trajectories. With technology increasingly available in schools and homes, understanding how to use it effectively remains essential. Future research may explore how advances in artificial intelligence could offer cost-effective, scalable ways to enhance educational outcomes.

For the full paper and an earlier summary of findings see Cueto et al., 2025 and VoxDev.

[1] These studies encompass different types of policies and programs, from computer-aided instruction to providing access to computers in schools and at home, and from range of different countries (Chile, India, Kenya, Peru, Romania).

[2] This is the argument in Lakdawala et al. (2023) who document limited impacts of internet access on schools after the first year, but growing and larger effects of internet access over time.

[3] Note that most teachers in the treatment group also received a one week 40-hour training that focused on how to operate the laptops and use them for pedagogical purposes.

[4] This estimate is significant at the 5% level based on its individual p-value, but just barely significant at the 10% level when accounting for multiple hypothesis testing with the academic achievement outcome.